Quirk: a drag-and-drop quantum circuit simulator

Quirk: a drag-and-drop quantum circuit simulator

2024/01/17&24

Quirk: a drag-and-drop quantum circuit simulator

Quirk: a drag-and-drop quantum circuit simulator

2024/01/17&24

Web site for the on-line version: https://algassert.com/quirk

Free, open source software: https://github.com/Strilanc/Quirk/

By Craig Gidney, "software engineer turned research scientist on the quantum computing team at Google".

Note: this is not an official Google product.

One can upload the code and install it on a PC.

How? See the README.md file, "Building" section.

Following the building process, one obtains at the end a single HTML file with everything inside (584 KB on my PC).

Quirk can be used to calculate:

But the calculation is right only up to a global phase factor, because two colinear non-nul vectors represent the same quantum state. As usually considered, Quirk uses normalised vectors, thus the only remaining free parameter is a phase factor $e^{i\theta}$.

Quirk calculate what a quantum circuit does for you!

See Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloch_sphere.

Hilbert space $H_2 = \mathbb{C}^2$ $\rightarrow$ Bloch sphere mapping:

$\left|\psi\right\rangle

= \left(\rho e^{i\eta}\right) \cdot \left( \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \left|0\right\rangle + \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi} \left|1\right\rangle \right)

= \left(\rho e^{i\eta}\right) \cdot \begin{pmatrix} \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \\ \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi} \end{pmatrix}$.

Quirk circuit with pseudo-random qubit.

Quirk circuit with these 6 quantum states.

Preservation of angles and left/right orientation $=$ rotation in Bloch sphere $=$ unitary operators in Hilbert space (Wigner's theorem).

Wigner's theorem: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wigner%27s_theorem.

Rotations around $z$, $x$ and $y$ axes: Quirk circuit for $z$, Quirk circuit for $x$ and Quirk circuit for $y$.

Pauli gates are rotation around $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes with angle $180^\circ$:

$\sigma_x = X = \begin{pmatrix}0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0\end{pmatrix}$,

$\sigma_y = Y = \begin{pmatrix}0 & -i \\ i & 0\end{pmatrix}$ and

$\sigma_z = Z = \begin{pmatrix}1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1\end{pmatrix}$.

Relation with quaternions with the identification $1 = I_2$, $i = (-iX)$, $j = (-iY)$ and $k = (-iZ)$:

Rotation around $z+x$ axis and Hadamard gate $H$: Quirk circuit for $z+x$. There are many gates that maps $\left|0\right\rangle \rightarrow \left|+\right\rangle$ and $\left|1\right\rangle \rightarrow \left|-\right\rangle$, but only one (up to a global phase) that maps $\left|0\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|+\right\rangle$ and $\left|1\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left|-\right\rangle$, the Hadamard gate $H$: Quirk circuit.

Unitary evolutions are reversible.

Inverse of rotation of axis $d$ and angle $\alpha$ $=$ rotation of axis $d$ and angle $-\alpha$ $\Rightarrow$ Inverses of unitary $2 \times 2$ matrices: Quirk circuits.

If $\alpha = 180^{\circ}$: the operators $X$, $Y$ ,$Z$ and $H$ are their own inverses: Quirk circuits.

The product of matrices does not commute in general: Quirk circuit with an example.

Measurement on $z$ axis: Quirk circuit.

Measuements on other axis:

Hilbert space for 2 qubits: $H_{4} = \mathbb{C}^4 = H_{2} \otimes H_{2}$.

Vector basis:

In Quirk, the vector $\left|b_1 b_0\right\rangle$ with $\left(b_1, b_0\right) \in \left\{0,1\right\}^2$ corresponds to the pair of qubits on upper wire $0$ and lower wire $1$ in states $\left|b_0\right\rangle$ and $\left|b_1\right\rangle$ respectively, i.e., least significant (qu)bits are above most significants (qu)bits: Quirk circuit.

Separable states: $\left|\Phi\right\rangle = \left|\psi\right\rangle \otimes \left|\chi\right\rangle \in H_{2} \times H_{2}$.

$\left|\Phi\right\rangle = \left|\psi\right\rangle \otimes \left|\chi\right\rangle

= \left( \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \left|0\right\rangle + \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi} \left|1\right\rangle \right)

\otimes \left( \cos\left(\frac{\theta'}{2}\right) \left|0\right\rangle + \sin\left(\frac{\theta'}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi'} \left|1\right\rangle \right)$

$= \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \cos\left(\frac{\theta'}{2}\right) \left|00\right\rangle$

$+ \cos\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) \sin\left(\frac{\theta'}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi'} \left|01\right\rangle$

$+ \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi} \cos\left(\frac{\theta'}{2}\right) \left|10\right\rangle$

$+ \sin\left(\frac{\theta}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi} \sin\left(\frac{\theta'}{2}\right) e^{i\varphi'} \left|11\right\rangle$.

The tensor product Hilbert space $H_{4} = \mathbb{C}^4 = H_{2} \otimes H_{2}$ is simply the vector space generated by $H_{2} \times H_{2}$, or by the vector basis $\left( \left|00\right\rangle, \left|01\right\rangle, \left|10\right\rangle, \left|11\right\rangle \right)$.

Entangled states are represented by (normalized) vectors that cannot be written as a seperable state, e.g., $\left|\Phi^+\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|00\right\rangle + \left|11\right\rangle \right)$.

Intuition that $H_{2} \times H_{2} \subsetneq H_{4} = H_{2} \otimes H_{2}$ using the freedom degrees for the projective spaces:

How to generate entangle states in Quirk?

$\Rightarrow$ Controlled gates.

Principle: if the most significant qubit is $\left|0\right\rangle$, the least significant qubit is unchanged, if if the most significant qubit is $\left|1\right\rangle$, the least significant qubit is inverted (NOT gate applied):

Matrix: $CNOT = \begin{pmatrix} I_2 & 0_2 \\ 0_2 & NOT \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

Quirk circuit for CNOT.

If we inverse the roles of the two qubits: Quirk circuit for $CNOT' = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

If we inverse the controlled qubit, activating the controlled gate when the control qubit is $\left|0\right\rangle$ instead of $\left|1\right\rangle$: Quirk circuit for $ACNOT = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

Any $2 \times 2$ gate $U = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \\ \end{pmatrix}$ can be controlled in the same way: $CU = \begin{pmatrix} I_2 & 0_2 \\ 0_2 & U \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & a & b \\ 0 & 0 & c & d \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

Quirk circuits for some controlled gates.

The rotation gates ($2 \times 2$ unitary matrices) and the CNOT gate can generate any quantum gates on 2 qubits.

More generally, any quantum gate (unitary operator) on $N$ qubits can be generated with rotation gates ($2 \times 2$ unitary matrices) and the CNOT gate.

A quantum program is the decomposition of a unitary operator acting on $N$ qubits into elementary rotation gate and CNOT gates...

The difficult aspects in quantum computing are (1) to find the interesting unitary operator to compute something interesting in an efficient way

and (2) to decompose it in a small number of small quantum gates!

Reminder: $\left|+\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0\right\rangle + \left|1\right\rangle \right) = H \left|0\right\rangle$ and $\left|-\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0\right\rangle - \left|1\right\rangle \right) = H \left|1\right\rangle$.

Bell states are states of pairs of qubits that are maximally entangled and form an orthonormal basis of $\mathbb{C}^4$:

Quirk circuits to produce these 4 Bell states with $CNOT'$ gate only.

Quirk circuits using Hadamard $H$ gate followed by $CNOT'$ gate to produce the Bell states.

Quirk circuits to produce the other Bell state by rotating one of the qubit of the Bell state $\left|\Phi^+\right\rangle$:

The Bell states being an orthonormal basis, we want to apply the right 4-dimensional unitary matrix $U$ such as, when measuring the two output qubits, we get:

We thus have, $\forall(a,b) \in \left\{0,1\right\}^2$, $U \times CNOT' \times \left(Id_2 \otimes H \right) \left|a\right\rangle \otimes \left|b\right\rangle = \left|a\right\rangle \otimes \left|b\right\rangle$.

This implies $U = \left( CNOT' \times \left(Id_2 \otimes H \right) \right)^\dagger = \left(Id_2 \otimes H \right) ^\dagger \times \left( CNOT' \right)^\dagger = \left(Id_2 \otimes H \right) \times \left( CNOT' \right)$: Quirk circuit.

The $CNOT'$gate follow by the $H$ gate followed by the two qubit measurments is called the Bell state measurement.

Swap gate $=$ qubit state exchange in a pair of qubit: $SWAP = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}$, Quirk circuit. It can be realized with 3 CNOT gates.

Square root of the swap gate: Quirk circuit. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_quantum_logic_gates#Non-Clifford_swap_gates.

Any $2^{N-1} \times 2^{N-1}$ gate $U_{2^{N-1}}$ for $N-1$ qubits can be controlled with a $N^{th}$ (most significant) qubit: $CU_{2^{N-1}} = \begin{pmatrix} I_{2^{N-1}} & 0_{2^{N-1}} \\ 0_{2^{N-1}} & U_{2^{N-1}} \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toffoli_gate. With classical bits, it is a universal gate for classical logic.

Toffoli gate $=$ CCNOT gate: $CCNOT = \begin{pmatrix} I_4 & 0_4 \\ 0_4 & CNOT \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

Quirk circuits for Toffoli gate.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fredkin_gate. With classical bits, it is a universal gate for classical logic, like the Toffoli gate.

Fredkin gate $=$ CSWAP gate: $CSWAP = \begin{pmatrix} I_4 & 0_4 \\ 0_4 & SWAP \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

Quirk circuits for Fredkin gate.

Generalization of Bell states to $N$ qubits: Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenberger%E2%80%93Horne%E2%80%93Zeilinger_state.

$\left|GHZ_N\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} + \left|1 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} \right) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0 \cdots_{\ (N)}\cdots 0\right\rangle + \left|1 \cdots_{\ (N)}\cdots 1\right\rangle \right)$, Quirk circuits.

Note: $\left|GHZ_2\right\rangle = \left|\Phi^+\right\rangle$.

GHZ states are used in quantum Byzantine agreement, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_Byzantine_agreement.

$\left|GHZ_3\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|000\right\rangle + \left|111\right\rangle \right)$ is the representative of one of the two classes of non-biseparable 3-qubit states, the other class being represented by $\left|W\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \left( \left|001\right\rangle + \left|010\right\rangle + \left|100\right\rangle \right)$, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W_state and Quirk circuits.

For $N$ qubits, $H_N = H^{\otimes N} = H \otimes \cdots_N \cdots \otimes H$.

$H_1 = H = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

$H_2 = H^{\otimes 2} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 \\ 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

$H_3 = H^{\otimes 3} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 \\ 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & 1 & -1 \\ \end{pmatrix}$.

Quirk circuits with qubits 0 as input: $H_N \left|0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} = H^{\otimes N} \left|0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} = \left(H \left|0 \right\rangle \right)^{\otimes N} = \left|+ \right\rangle^{\otimes N} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^N}} \sum_{n=0}^{2^N-1} \left|n \right\rangle$. This a a way to try all the combination of classical input bits (encoded by integers $n = 0$ to $2^N-1$) at the same time using this balanced superposition of all classical states: the "parallelization capability" of quantum computing...

Quantum version of the classical Fourier transform, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_Fourier_transform.

For dimension $M$, $QFT_M = \frac{1}{\sqrt{M}} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \\ 1 & \omega_M & \omega_M^2 & \omega_M^3 & \cdots & \omega_M^{M-1} \\ 1 & \omega_M^2 & \omega_M^4 & \omega_M^6 & \cdots & \omega_M^{2(M-1)} \\ 1 & \omega_M^3 & \omega_M^6 & \omega_M^9 & \cdots & \omega_M^{3(M-1)} \\ \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots & \cdots \\ 1 & \omega_M^{M-1} & \omega_M^{2(M-1)} & \omega_M^{3(M-1)} & \cdots & \omega_M^{(M-1)(M-1)} \\ \end{pmatrix}$ where $\omega_M = e^{\frac{2\pi i}{M}}$.

For $N$ qubits, $M = 2^N$ (classical: Fast Fourier Transform).

Quirk circuits with qubits 0 as input: $QFT_{2^N} \left|0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^N}} \sum_{n=0}^{2^N-1} \left|n \right\rangle = H_N \left|0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N}$. Like with Hadamard gates, this a a way to try all the combination of classical input bits (encoded by integers $n = 0$ to $2^N-1$) at the same time using this balanced superposition of all classical states: the "parallelization capability" of quantum computing...

$QFT_2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & \omega_2 \\ \end{pmatrix} = H = H_1$ because $\omega_2 = e^{\pi i} = -1$, but, $\forall N \geq 2$, $QFT_{2^N} \neq H_N$: Quirk circuits with psuedo-random inputs.

Realization of the QFT gate with single-qubit gates and controlled single gates: Quirk circuit for $QFT_{2^6}$. Approximation of the QFT gate: Quirk circuit for $QFT_{2^8}$.

Use of $H$, $X^{\pm\frac{1}{2}}$ or $Y^{\pm\frac{1}{2}}$ gate then measurement gate: Quirk circuit.

What are the qubit states $\varphi$ that give a probability $P = \frac{x}{100}$ to measure the state $1$?

The qubi measurement formula gives $P = \frac{x}{100} = \mathbf{P}\left[\varphi \rightarrow 1\right] = 1 - \mathbf{P}\left[\varphi \rightarrow 0\right] = 1 - \cos^2\theta_{Hilbert}\left(\varphi,0\right) = 1 - \cos^2 \left( \frac{1}{2} \cdot \theta_{Bloch}\left(\varphi,0\right) \right)$.

Use of $X^{\pm f(t)}$ or $Y^{\pm f(t)}$ gate with $f(t) = \frac{2}{\pi} \cdot \arccos \left( \sqrt{1 - \frac{x}{100}} \right)$, then measurement gate: Quirk circuit (if $x = 100$%, we have $f(t) = 1$ $\Rightarrow$ $X = X^1$ or $Y = Y^1$ gate).

Use of $N$ 50%/50% random classical bit generators: Quirk circuits with $N \in \left\{1, 2, 3, \cdots, 9, 10\right\}$.

For example, for $M = 3$, one can measure 2 qubits, the first one implementing a random bit generator with probability 1/3 and the second one implementing a random bit generator with probability 1/3: Quirk circuit. More compact Quirk circuits: Quirk circuits.

Compact Quirk circuits for $M \in \left\{3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8\right\}$ and $M \in \left\{9, 10, 12, 14\right\}$.

For example, for the probability vector $P = \left(\frac{5}{100}, \frac{10}{100}, \frac{10}{100}, \frac{30}{100}, \frac{45}{100}\right)^\mathrm{t}$: Quirk circuit.

Classical cloning is feasible but not quantum cloning: Quirk circuit.

Using Toffoli, CNOT and NOT gates: Quirk circuit.

Using Fredkin gates: Quirk circuit.

Using Toffoli (and CNOT) gates: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adder_(electronics)#Quantum_adders and Quirk circuit.

Using Fredkin gates: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fredkin_gate#Example and Quirk circuit.

Quantum phenomenon: Noise $=$ Interaction with the environment

A qubit in fully depolarized state (depolarization probability 1, $p = 0$) has the following density matrix:

$\forall \varphi, \ \rho_{\varphi, 0}

= \frac{1}{2} \cdot \left|\varphi\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right| + \frac{1}{2} \cdot \left|\varphi^\bot\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi^\bot \right|

= \frac{1}{2} \cdot Id_2.$

A qubit $\varphi$ in partially depolarized state with depolarization probability $1-p$,

where $p \in \left]0, 1\right[$, has the following density matrix:

$\rho_{\varphi, p}

= p \cdot \left|\varphi\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right| + (1-p) \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot Id_2

= \frac{1+p}{2} \cdot \left|\varphi\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right| + \frac{1-p}{2} \cdot \left|\varphi^\bot\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi^\bot \right|.$

A qubit $\varphi$ in pure state (depolarization probability 0, $p = 1$), has the following density matrix:

$\rho_{\varphi, 1}

= \left|\varphi\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right|.$

$F = \frac{1+p}{2} \in \left[\frac{1}{2}, 1\right]$ is the fidelity of the qubit (fidelity $=$ probability to measure the expected state).

Quirk circuit for $\rho_{\ 0,\ 0}$ $\Rightarrow$ One of the qubit of a Bell pair... An unpolarized qubit is a pure qubit that completely interacted with its (uncontolled) environment.

Quirk circuit for $\rho_{\ 0,\ 0.6}$ (fidelity $80$%), another Quirk circuit using $\rho_{\varphi, p} = p \cdot \left|\varphi\right\rangle \left\langle \varphi \right| + (1-p) \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot Id_2$.

Quirk circuit for $\rho_{\ 0,\ p}$, with $p \in \left\{ 1, 0.9, 0.75, 0.5, 0.25, 0 \right\}$, Quirk circuit with $p \in \left[0,1\right]$.

Quirk circuit for $\rho_{\ \varphi,\ 0.6}$ (fidelity $80$%).

If one controls the environment, one can remove the noise (but, in practice, one cannot control the environment...): Quirk circuit for $\rho_{\ \varphi,\ 0.6}$ (fidelity $80$%).

Quantum channels are linear maps on density matrices: $CH_{p} : \mathcal{DM} \rightarrow \mathcal{DM}$.

Depolarization channel $DCH_{p}$ with probability of depolarization $1-p$ on qubits is such as $DCH_{p} \left(\rho\right) = p \cdot \rho + (1-p) \cdot Id_2$.

Quirk circuit for pseudo-random pure qubit at the input of depolarizing quantum channel with probability of depolarization $1-p = 40$%. Alternative Quirk circuit. Simplified Quirk circuit if the input qubit is in Oxz plane.

The serial concatenation of two depolarizing quantum channels with depolarization probabilities $1-p_1$ and $1-p_2$ is equal to a single depolarizing quantum channels of fidelity with depolarization probabilities $1-p$ where $p = p_1 \cdot p_2$. Illustration with $p_1= 0.8$, $p_2= 0.6$, $p = p_1 \cdot p_2 = 0.48$: Quirk circuit.

Noisy Bell states can be obtained applying a depolarization quantum channel on one of the two qubits of the pair with depolarization probability $p$. The fidelity is $F = \frac{1+3p}{4}$, i.e., $p = \frac{4F-1}{3}$.

Illustration with $\Phi^+$ and $F = 70$%, i.e., $p = 60$%: Quirk circuit.

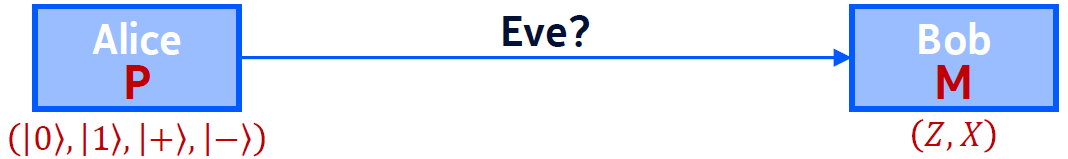

BB84: Prepare (P) and Measure (M) protocol for QKD

Charles H. Bennett and Gilles Brassard, "Quantum cryptography: Public key distribution and coin tossing," in Proceedings of the International Conference on Computers, Systems and Signal Processing, pp. 175-179, Bangalore (1984), https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.06557, republished in Theoretical Computer Science, vol. 560 (2014), pp. 7–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcs.2014.05.025.

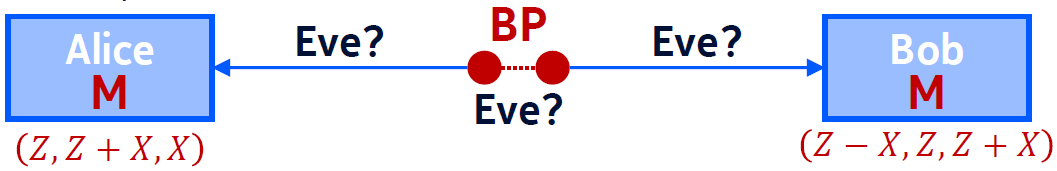

BBM92: BBM92: Entanglement-based protocol $\Rightarrow$ Bell Pair (PB) creation and Measures (M) for QKD

Charles H. Bennett, Gilles Brassard, and N. David Mermin, "Quantum cryptography without Bell’s theorem," Phys. Rev. Lett. 68:557-559 (1992), https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.557.

E91: Entanglement-based protocol $\Rightarrow$ Bell Pair (PB) creation and Measures (M) for QKD

E91 requires Bell's inequalities... See below §8.4 "Bell's inequality violation by quantum physics"

Artur K. Ekert, "Quantum cryptography based on Bell's theorem," Phys. Rev. Lett. 67:661-663 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.661.

Ludovic Noirie and Rémi Varloot, "Authentication Through Error Estimation in QKD," Globecom 2023, PDF of the paper.

See the article for details, or the LINCS seminar presentation 10/01/2024.

Quirk circuit for Eve's man-in-the-middle attack if the indexes selected by Alice or Bob are not one-time-pad encrypted with pre-shared secrete key (as represented in the figure 2 of the paper).

Grover's algorithm = quantum search algorithm, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grover%27s_algorithm.

For $N \in \mathbb{N}\setminus\left\{0\right\}$,

the generic oracle corresponding to the function $f: \left\{0, 1, 2, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\} \rightarrow \left\{0,1\right\}$

if the quantum operator $U_f$ in the Hilbert space $\mathbb{C}^{2^{N+1}} = \mathbb{C}^{2^N} \otimes \mathbb{C}^{2}$ such as:

$\forall n \in \left\{0, 1, 2, 3, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\}$, $\forall b \in \left\{0,1\right\}$:

$\ \bullet\ f(n)=0$ $\Rightarrow$ $U_f \left( \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle \right) = \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle$,

$\ \bullet\ f(n)=1$ $\Rightarrow$ $U_f \left( \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle \right) = \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| \neg b \right\rangle$,

i.e., in a more compact formula, $U_f \left( \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle \right) = \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \oplus f(n) \right\rangle$,

where $\left| n = b_{N-1} \cdots b_2 b_1 b_0 \right\rangle

= \left| b_{N-1}\right\rangle \otimes \cdots \otimes \left| b_2\right\rangle \otimes \left| b_1\right\rangle \otimes \left| b_0\right\rangle$.

The oracle acts like a black box that one can test, with classical inputs or quantum inputs.

With classical inputs $n \in \left\{0, 1, 2, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\}$, one can get the value $f(n)$ with:

$U_f \left( \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| 0 \right\rangle \right) = \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| f(n) \right\rangle$.

With quantum inputs, e.g., superposition of classical inputs for parallelization, one can expect to get information on some properties of $f$ faster than by testing only with classical inputs.

For quantum search problem, the function $f: \left\{0, 1, 2, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\} \rightarrow \left\{0,1\right\}$ is such as,

for $m \in \left\{0, 1, 2, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\}$:

$\ \bullet\ \forall n \in $ such as $n \neq m$, $f(n)=0$,

$\ \bullet\ f(m)=1$.

The corresponding oracle $U_f$ is such as:

$\forall n \in \left\{0, 1, 2, 3, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\}$, $\forall b \in \left\{0,1\right\}$:

$\ \bullet\ n\neq m$ $\Rightarrow$ $U_f \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle \otimes = \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle$,

$\ \bullet\ U_f \left| m \right\rangle \otimes \left| b \right\rangle \otimes = \left| m \right\rangle \otimes \left| \neg b \right\rangle$.

Oracle $U_f$ for the quantum search Grover's algorithm: Quirk circuit for $N=5$.

One can check that $U_f \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| - \right\rangle = \left( V_m \left| n \right\rangle \right) \otimes \left| - \right\rangle$,

where $V_m \left| n \right\rangle = (-1)^{f(n)} \left| n \right\rangle$:

$U_f \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| - \right\rangle

= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} U_f \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| 0 \right\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} U_f \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| 1 \right\rangle

= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| 0 \oplus f(n) \right\rangle - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} U_f \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| 1 \oplus f(n) \right\rangle

= (-1)^{f(n)} \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| - \right\rangle$.

Quirk circuit for $N=5$.

One can use the black box $U_f$ with classical inputs $n \in \left\{0, 1, 2, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\}$ to evaluate $f(n)$ with:

$U_f \left( \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| 0 \right\rangle \right) = \left| n \right\rangle \otimes \left| f(n) \right\rangle$.

The evaluation is succesful when $f(n) = 1$.

This requires on average $2^N/2$ evaluation, i.e., $O\left(2^N\right)$.

Realization of the quantum operator $V_N = I_{2^N} - 2 \left| 0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} \left\langle 0 \right|^{\otimes N}

= -\left( 2 \left| 0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} \left\langle 0 \right|^{\otimes N} - I_{2^N} \right)$:

$\ \bullet \ V_N \left| 0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N} = - \left| 0 \right\rangle^{\otimes N}$,

$\ \bullet \ \forall n \in \left\{1, 2, \cdots, 2^N-1\right\}$, $V_N \left| n \right\rangle = \left| n \right\rangle$.

Quirk circuit realizing $V_5$ with an auxiliary qubit,

Quirk circuit for alternative vizualization of sign change with a superposed state.

The probability to measure $\left| m \right\rangle$ with $r$ repetitions is

$p(2^N,r) = \sin^2\left( \left(r+\frac{1}{2}\right) \cdot 2\arcsin\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^N}}\right) \right)$.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grover%27s_algorithm#Geometric_proof_of_correctness for a demonstration.

The first near-optimal measurement is therefore for $r \approx \frac{\pi\sqrt{2^N}}{4}$.

This first near-optinal measurement gives:

$\ \bullet \ p(2^N,r) \approx 94.53\%$ for $N = 3$,

$\ \bullet \ p(2^N,r) \approx 96.13\%$ for $N = 4$,

$\ \bullet \ p(2^N,r) > 98\%$ for $N \geq 5$,

$\ \bullet \ p(2^N,r) > 99\%$ for $N \geq 9$,

$\ \bullet \ p(2^N,r) > 99.99\%$ for $N \geq 15$,

$\ \bullet \ p(2^N,r) > 99.9999\%$ for $N \geq 20$, etc.

Grover algorithm using $U_f$: Quirk circuit for $N=5$, $2^N=32$, Alternative Quirk For $N = 5$, $\frac{\pi\sqrt{2^n}}{4} \approx 4.443$ and $p(32,4) = 99.9182\%$.

Quadratic speed-up:

Thus, for large $N$, with a very high probability, one needs only $O\left(\sqrt{2^N}\right) = O\left(2^{\frac{N}{2}}\right)$ with quantum search vs. $O\left(2^N\right)$ with classical search.

Note that the search is still exponential with the number of bits $N$...

Applications:

This quadratic speed-up of the Grover's algorithm can be applied to quadratically accelerate some problems compared to their classical versions:

Quantum circuits for Shapley value astimation as presented by Ian Burge in his talk at LINCS 2023/10/04.

Source:

The above circuits uses the E_2 gate, which is the perfect gate that gives the exact values, while U2 is the the approximated gate used by I. Burge et al.

The generalization with the approximation by U$n$ where $n = \left\lceil log_2(N) \right\rceil$, $N$ being the number of voters, works for all $N$.

Some ways to create the F_n gate for F_4 (5 voters case): inefficient Quirk circuit , more efficient Quirk circuit with explicit matrices and more efficient Quirk circuit with usual gates

Some calculators for Shapley values:

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interpretations_of_quantum_mechanics. In bold: the ones I consider the most important ones (subjective!).

Other interpretations: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minority_interpretations_of_quantum_mechanics.

Relational interpretation of quantum mechanics [Rovelli 1996], see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relational_quantum_mechanics.

Carlo Rovelli, "Relational Quantum Mechanics", Int J Theor Phys 35, 1637–1678 (1996), https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02302261, https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9609002.

Carlo Rovelli, "The Relational Interpretation of Quantum Physics", Oxford Handbook of the History of Interpretation of Quantum Physics (2022), Part V, §43, https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-the-history-of-quantum-interpretations-9780198844495, https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.09170.

The principles of RQM (my reformulation, in particular point 3):

The consequences of these principles:

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_logic.

There were some successive mathematical results that show how the structure of Hilbert space that we have in quantum mechanics can be derived mathematically from the logical structure of quantum mechanics which is an orthomodular lattice.

Some definitions:

Garrett Birkhoff and John von Neumann, "The logic of quantum mechanics," Annals of Mathematics, Second Series, 37(4):823–843 (1936), https://doi.org/10.2307/1968621.

Birkhoff and von Neumann showed in 1936 that the logical structure of experimental tests in classical mechanics forms a Boolean latice, but the logical structure of experimental tests in quantum mechanics forms an orthomodular lattice.

For quantum mechanics, the elements of the orthomodular lattice are the vectorial subspaces $E$ of the Hilbert space $V$ that are stable by orthogonality, this orthogonality corresponding to the orthocomplement operator $\bot$ of the lattice: $E = E^{\bot\bot}$:

Birkhoff and von Neumann also showed that, for any orthomodular lattice for which the rank is finite and greater than or equal to 4, then it can be represented by a vector space $V$ on some (maybe not commutative) field $K$ equipped with a conjugation operation $^\star$ that induces an hermitian-like product $\left\langle \cdot | \cdot \right\rangle$ on the vectore space $V$, like in Hermitian spaces on complex numbers ($=$ Hilbert spaces on $\mathbb{C}$ of finite dimension). Such vector space $V$ is called a generalized Hilbert space because the structure is similar to Hilbert spaces.

Constantin Piron, "Axiomatique quantique," Helvetica physica acta, 37(4-5):439 (1964), https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=hpa-001%3A1964%3A37%3A%3A443, https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=hpa-001%3A1964%3A37%3A%3A774 (in French!).

Piron extended the result of Birkhoff and von Neumann for infinite rank with infintie dimensional vector spaces in 1964.

Maria Pia Solèr, "Characterization of Hilbert spaces by orthomodular spaces," Communications in Algebra, 23(1):219–243 (1995), https://doi.org/10.1080/00927879508825218

See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sol%C3%A8r%27s_theorem.

Solèr showed that, if we suppose the existence of an infinite family of orthogonal vectors $v_n \in V$, $n \in \mathbb(N)$,

with same norm $\left\langle v_n | v_n \right\rangle = \left\langle v_0 | v_0 \right\rangle$ $\forall n \in \mathbb(N)$,

then $K \in \left\{ \mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C}, \mathbb{H} \right\}$, i.e.,

$V$ is a Hilbert space on the real numbers, the complex numbers or the quaternions.

Articles reviewing Maria Pia Solèr's result:

Note that, because of the representation of the system $S$ made of subsystems $S_A$ and $S_B$ must be represented by a tensor product $V_S = V_A \otimes V_B$, the field $K$ must be commutative, which excludes the quaternion case: $K \in \left\{ \mathbb{R}, \mathbb{C} \right\}$.

The real case is excluded when one consider the continusous evolution of a quantum system which must have eigenstates with different energies: this is not possible if $K$ is the field of real numbers (see also Renou et al., "Quantum theory based on real numbers can be experimentally falsified", §8.5 below). Thus $K = \mathbb{C}$.

Categorical equivalences between orthomodular lattice structures, projective geometries and generalized Hilbert spaces

Isar Stubbe and Bart Van Steirteghem, "Propositional systems, Hilbert lattices and generalized Hilbert spaces," Handbook of Quantum Logic and Quantum Structures, pages 477–523 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044452870-4/50033-9, https://arxiv.org/abs/0710.2098.

Inside an isolated box that is isolated from any external observer $O_{out}$:

We, as external observer $O_{out}$, do not know if the cat is dead or alive, it is in a "superposition".

The composite system made of the atom, the Geiger counter, the mechanism releasing the poison, the cat and the internal observer in the box is in state $ \left| GHZ_5 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0\right\rangle_{atom} \otimes \left|0\right\rangle_{Geiger} \otimes \left|0\right\rangle_{poison} \otimes \left|0\right\rangle_{cat} \otimes \left|0\right\rangle_{O_{in}} + \left|1\right\rangle_{atom} \otimes \left|1\right\rangle_{Geiger} \otimes \left|1\right\rangle_{poison} \otimes \left|1\right\rangle_{cat} \otimes \left|1\right\rangle_{O_{in}} \right)$ for any external observer $O_{out}$.

The cat seems to be dead and alive at the same time...

The Quirk circuit shows how to implement the Shrödinger's cat thought experiment, using the CNOT gate to encode internal measurement or physical activation through subsystem interactions.

Usual objection against this paradox:

The cat is a macroscopic system and cannot be modelised with a single qubit. It is subject to many interaction with its environment which implies decoherence.

Because of the reversibility of the Shrödinger equation, the observer inside the box can resuscitate the cat, which is absurd:

Quirk circuit.

The state is relative to the observer en encode the knowledge of the outside observer: the cat is dead or alive, the outside observer does not know...

As outside observer $O_{out}$, before we observe what is in the box, we do not know if the cat is dead or alive with state $\left| GHZ_5 \right\rangle$,

while the inside observer $O_{in}$ sees if the cat is dead with state $\left|1\right\rangle_{cat}$ or alive with state $\left|1\right\rangle_{cat}$.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einstein%E2%80%93Podolsky%E2%80%93Rosen_paradox.

The EPR thought experimen, performed with electron-positron pairs (Bohm's variant).

A source (center) sends particles toward two observers, electrons to Alice (left) and positrons to Bob (right), who can perform spin measurements.

Initial Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen version of the EPR paradox with continuous variables

Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?" Phys. Rev. 47:777-780 (1935), https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.47.777.

The authors use an entangled pair of particles and consider theirs momentums and their positions as conjugate observables.

Bohm's variant of the EPR paradox with discrete variables

David Bohm and Yakir Aharonov, "Discussion of Experimental Proof for the Paradox of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky", Phys. Rev. 108(4):1070-1076 (1957), https://doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRev.108.1070.

The author uses an entangled pair of $\frac{1}{2}$-spin particles (positron - electron) in Bell state $\left|\Psi^-\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0\right\rangle \otimes \left|1\right\rangle - \left|1\right\rangle \otimes \left|0\right\rangle \right)$. Alice receives one of the particles and performs $Z$-axis spin-mesurement while Bob, in another location, receives the other particle and performs $X$-axis spin-mesurement.

One can replace the $\left|\Psi^-\right\rangle$ Bell state by the $\left|\Phi^+\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left( \left|0\right\rangle \otimes \left|0\right\rangle + \left|1\right\rangle \otimes \left|1\right\rangle \right)$ Bell state:

Paradox:

Spooky action at distance (Albert Einstein): The measurement of Alice change the state of the particle in Bob's location "instantaneously", and this state depends on the choice of the measurement axis by Alice. This seems contradictory with the special relativity theory for which no information can travel faster than the speed of light.

EPR hypotheses:

The result of this thought experiment is that at least one of the 3 hypotheses is wrong:

Relational interpretation of the original EPR paradox

See Matteo Smerlak and Carlo Rovelli, "Relational EPR," Found.Phys.37:427-445 (2007), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10701-007-9105-0, https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0604064, for a good discussion about this.

The state of the particle in Bob's location is not measured by Alice, but inferred with the information correlation from the initial Bell state. With the relational interpretation of quantum mechanics, this state is relative to Alice, Bob may have another state for his particle. Thus 1 is wrong: the state of this particle, even known with probability 100% by Alice, is not universally valid.

Same initial configuration as above, but, instead of considering measurements by Alice according to $Z$ or $X$ axes, we consider the configuration where Alice measures according to $Z$ axis and Bob measures according to $X$ axis.

We suppose that the distance between Alice and Bob is long enough so that the measurement of Alice (resp. Bob) occurs before she (resp. he) receives the results of the measurmeent of Bob (resp. Alice).

We can consider the two following cases:

Alice measures before Bob: the state of the two particles after Alice's measurement and before Bob's measurement is $\left|0\right\rangle \otimes \left|0\right\rangle$ with probability 50% or $\left|1\right\rangle \otimes \left|1\right\rangle$ with probability 50%, Quirk circuit.

Bob measures before Alice: the state of the two particles after Bob's measurement and before Alice's measurement is $\left|+\right\rangle \otimes \left|+\right\rangle$ with probability 50% or $\left|-\right\rangle \otimes \left|-\right\rangle$ with probability 50%, Quirk circuit.

Question: Who measures first?

Answer: This depends of the reference space-time frame! (special relativity)

For some reference space-time frames, Alice measures first, for other, Bob measures first.

Paradox (if one consider absolute quantum state): What is then the right state?

$\left|0\right\rangle \otimes \left|0\right\rangle$ / $\left|1\right\rangle \otimes \left|1\right\rangle$

or $\left|+\right\rangle \otimes \left|+\right\rangle$ / $\left|-\right\rangle \otimes \left|-\right\rangle$?

Relational intermpretation of quantum mechanics (relative quantum state): Both are valid!

The state can be different because it is relative to the observer, and this is precisely the case here!

Note: after receptions of the results of the Bob's measurement by Alice and Alice's measurement by Bob, the state is $\left|0\right\rangle \otimes \left|+\right\rangle$ / $\left|0\right\rangle \otimes \left|-\right\rangle$ / $\left|1\right\rangle \otimes \left|+\right\rangle$ / $\left|1\right\rangle \otimes \left|-\right\rangle$ (with probability 25% for each case) for both Alice and Bob.

Related wikipedia pages:

Principle:

Calculation of $CHSH(Z,X;X+Z,X-Z) = \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(Z)}(-1)^{b(Z+X)}\right] + \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(Z)}(-1)^{b(Z-X)}\right] + \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(X)}(-1)^{b(Z+X)}\right] - \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(X)}(-1)^{b(Z-X)}\right]$:

$(1)$ For classical bits $a$ and $b$, $(-1)^a (-1)^b = (-1)^{a \oplus b},$ which gives:

$CHSH(Z,X;X+Z,X-Z) = \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(Z) \oplus b(Z+X)}\right] + \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(Z) \oplus b(Z-X)}\right] + \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(X) \oplus b(Z+X)}\right] - \mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a(X) \oplus b(Z-X)}\right]$.

$(2)$ Calculation of $\mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a \oplus b}\right]$:

$\mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a \oplus b}\right] = 1 \times \mathbf{P}\left[a \oplus b = 0\right] + (-1) \times \mathbf{P}\left[a \oplus b = 1\right] = 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[a \oplus b = 0\right] -1 = 1 - 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[a \oplus b = 1\right].$

Using $\mathbf{P}\left[a \oplus b = 1\right] = \mathbf{P}\left[C\textrm{-}NOT(a,b)=1\right]$ (classical XOR) and $\mathbf{P}\left[a \oplus b = 0\right] = \mathbf{P}\left[AC\textrm{-}NOT(a,b)=1\right]$ (classical XNOR $=$ NOT $\circ$ XOR):

$\mathbf{E}\left[(-1)^{a \oplus b}\right] = 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[AC\textrm{-}NOT(a,b)=1\right] -1 = 1 - 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[C\textrm{-}NOT(a,b)=1\right]$.

$(3)$ Finally, we have:

$\begin{array}[rcl]{} CHSH(Z,X;X+Z,X-Z) &=& \left( 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[AC\textrm{-}NOT(a(Z),b(Z+X))=1\right] -1 \right) \\ &+& \left( 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[AC\textrm{-}NOT(a(Z),b(Z-X))=1\right] -1 \right)\\ &+& \left( 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[AC\textrm{-}NOT(a(X),b(Z+X))=1\right] -1 \right)\\ &+& \left( 2 \cdot \mathbf{P}\left[C\textrm{-}NOT(a(X),b(Z-X))=1\right] -1 \right). \end{array}$

$(4)$ If the four probabilities are equal to the same value $P$, then $CHSH(Z,X;X+Z,X-Z) = 8 P - 4$:

Quirk circuit

to prove that the Bell's inequality is violated:

The four probabilities are equal to the same value $P = \frac{2 + \sqrt{2}}{4} \approx 0.8535534 > 0.75$.

Quick compact circuits for the different Bell states:

Version with random generators for $CHSH_{\Phi^+}(Z,X;Z+X,Z-X) = CHSH(Z,X;Z+X,Z-X)$: Quirk circuit.

With noisy Bell state having fidelity $F_{BP} = 80$%, we get $P \approx 0.7592725> 0.75$: Quirk circuit.

[RTW+2021] Renou, M.-O., Trillo, D., Weilenmann, M. et al. Quantum theory based on real numbers can be experimentally falsified. Nature 600, 625–629 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04160-4.

Their scheme use entanglement swapping (= entanglement teleportation). Quantum circuit for entanglement swapping: Quirk circuit. Alternative Quirk circuit showing the 4 Bell states.

Quantum circuit to prove that complex numbers are required in quantum physics, with $b \in B = \left\{(0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1)\right\}$ represent the couple of classical bits measured by Bob after entanglement swapping:

We have $T = C_1 + C_2 + C_3 = 6\sqrt{2} \approx 8.49$.

The authors [RTW+2021] proved that, for any quantum theory based on real numbers instead of complex numbers, one has $T \leq 7.6605$. This is the most difficult part of the article! The proof require numerical computing.

Recent experiments (*) show that $T > 7.6605$ by $>4.5\sigma$, proving that the real world requires complex numbers...

(*) See Marc-Olivier Renou, Antonio Acín and Miguel Navascués:

Avshalom C. Elitzur and Lev Vaidman, "Quantum mechanical interaction-free measurements,"

Foundations of Physics. 23 (7): 987–997 (1993),

or arXiv:hep-th/9305002.

See also Wikipedia, "Elitzur–Vaidman bomb tester".

Daniela Frauchiger and Renato Renner, "Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself", Nature Communications, (2018) 9:3711.

This is an extension of the Wigner’s Friend paradox, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wigner%27s_friend.

Questions?